What do we mean by local politics? Well, all the stuff that takes place in and around local government bodies and local party branches. But also a lot of what’s going on as politicians at district and village level interact and engage with government and party offices in Kathmandu.

This crash course is not necessarily the “whole story” or even the correct one. Indeed, local politics is complex and full of surprises once you actually meet the politicians themselves and the people they interact with. Go to any village and you sometimes get surprised, at least we are time and again.

We’ll be adding to the sections of this crash course along the way and maybe even new sections. Feel like sharing some of your insights – or correcting some of our observations? We’d love to post your input! The idea of this compilation is not to conclude but to initiate an interactive web-page.

We believe that it’s good to know about politics where the far majority of the country’s population live – in the districts and villages. This crash course is not made with any particular target group in mind but is simply for anybody who’s interested to know about Nepalese politics or to change it.

If you know a lot already, please feel welcome to add to the crash course. If you don’t, we hope you’ll find it informative and entertaining. Just scroll down and/or click on the headlines below – enjoy!

List of Contents

Chapter 1…………………………………………..The Setting: Some Framework Conditions

Chapter 2…………………………………………..Actors and Players in Local Politics

Chapter 3…………………………………………..Needs and Interests

Chapter 4…………………………………………..Values and Norms

Chapter 5…………………………………………..Capacity and Power of Local Governments

Chapter 6…………………………………………..Serving the People: Development Work

Chapter 7…………………………………………..Favouritism in the Distribution of Development

Chapter 8…………………………………………..Decision-making at Formal Meetings

Chapter 9…………………………………………..Serving the People: Personal Benefits

Chapter 10…………………………………………Elections: How Politicians Win Votes

Chapter 11…………………………………………Accessing Resources to Provide Benefits

Chapter 12…………………………………………What Drives Local Politicians

Chapter 13…………………………………………Candidate Selection

Chapter 14…………………………………………Corruption at Local Level: Misappropriation of Resources

Chapter 15…………………………………………Why Misappropriate Resources: Motives of the Politicians

Chapter 16…………………………………………Bureaucracy: Friend and Foe in Local Politics

Chapter 17…………………………………………Struggles for Power: Local Politics at Its Most Intense

Chapter 18…………………………………………Other Aspects of Local Politics – Feel free to Add!

Chapter 19…………………………………………Comparative Observations on Local Politics in Nepal

Chapter 1: The Setting: Some Framework Conditions

It’s simply difficult to jump right into the way local politics in Nepal works without first being a bit familiar with the setting in which it takes place. What do we mean by “setting”? Well, it could include a lot of things. But we are thinking of a handful of conditions. Read here to begin with that.

First thing first: The District

It’s in the districts that local politics takes place. So, first of all, it’s relevant to know what a district looks like. In fact, there is no way of knowing how local politics in Nepal works without first being familiar with the “district” in the countryside: it’s in the districts that most local politics takes place!

How many districts are there? Well, the number is still 75 altogether, like it was when Nepal was first sub-divided into modern administrative districts back under the Partyless Panchayat System. That was in the early 1960s. Nepal even had districts before that. So it’s part of a long tradition.

A district is in turn further sub-divided into a number of “VDCs”. VDCs – the abbreviation of Village Development Committees – are the most immediate context of most Nepalese citizens: it’s where all villagers live! Some will think of VDCs as a kind of rural communes or municipalities.

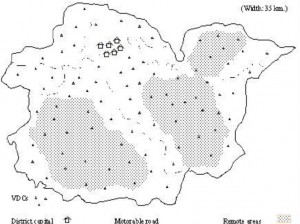

There is almost 4000 VDCs altogether. They are each comprised of typically one to two dozen villages. The boundaries of the VDCs can often be traced back to the administrative divisions of the 1960s too. Opposite is a drawing of a typical district with a district town surrounded with VDCs.

The district town – there are typically one or two – is the most populated settlement in a district. The VDCs in the surrounding hinterland vary in numbers: there can be anything from thirty or so (e.g. Chitwan) to eighty or more (e.g. Kavre), and some VDCs will be nearby, others more remote.

The population of Nepal’s districts varies but is typically between 200.000 and 300.000. The VDC populations vary just as much: its biggest in the Terai with 10.000 inhabitants or more, smaller in the Hills in the interior, and smallest in the Mountains.

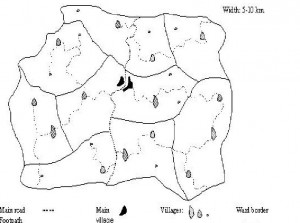

It’s useful to have an image of a VDC. So opposite is a sketch of a typical example. All VDCs are subdivided into nine sub-areas called “wards” each comprised of typically two to three villages.

One of the villages in a VDC is the main village: it’s where you’ll find the high-school, the health post, the VDC office, and most local shops and restaurants. It is in a sense the “capital” of the VDC.

In short, a VDC is like a mini-district. It too has a “capital” and is surrounded with villages, some of which are easy to reach, located near the local “capital” and roads, while others are more remote.

Moving about in a district: Transportation and communication

How do you move about in districts and villages as a local politician? Well, just like everybody else, the answer would be. But we think this part of the setting is important too. Politicians need to move around quite a bit, and anybody who’s tried to reach a remote village knows how that can be!

It can take hours, if not a day or longer, to make it to a village far away from the district town, and so it can for a politician. The difference between most villagers and an active local politician is how often it’s necessary to make the trip either from the village to the town or Kathmandu or back again.

Politicians in Nepal often travel a lot between towns and villages, at least if they are ambitious and trying to be popular locally. What does that mean exactly? Details will follow in a later section. But it’s well-known that politicians make use of links and connections and to do that requires mobility!

It has clearly become easier in recent years to move about within a district in Nepal. Since the 1990s, the roads network has been greatly expanded in many districts, and in many VDCs too. It’s still just bumpy gravel roads in many cases but good enough for a jeep, even a bus, to get through.

It’s also become easier to make contact via telephone. Mobile phone towers or at last telephone cables have been expanded. It’s not uncommon to see a villager with a mobile phone, although the connection might still be slow and unreliable. In addition, the Internet has also reached more areas.

FM stations have increased in geographical coverage too. It’s just a decade ago when we tuned in to one of the first FM stations, based in Kathmandu. Since then, a veritable mushrooming of local radio stations has occurred, and also many villagers can tune in, typically on small transistor radios.

Roads and telephone connections, though, as well as Internet and FM stations, are still concentrated around the towns, in the Terai, and in the most populated Hill areas. In most districts, it still takes a lot of sweat and time to reach most villages. So, it often remains a cumbersome and slow activity.

Organisational Set-up: Local Governments and Party Branches

Politicians at district and village level hold positions as “politicians” (as representatives of their parties) in two main types of organisations: local governments and local party branches. So another basic part of the setting is the organisational set-up of these local bodies and the positions in them.

Local Governments: The DDCs and VDCs

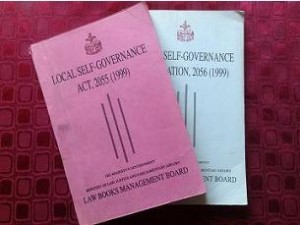

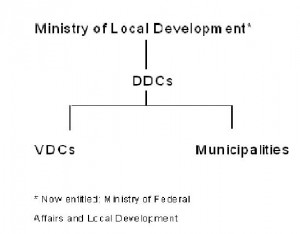

The local governments in a rural district in Nepal can be illustrated as done opposite. The Local Self-governance Act of 1999, which is still the main legal framework, defines three main local bodies: the DDCs, the VDCs, and the local bodies in the bigger district towns, the municipalities.

The local governments in a rural district in Nepal can be illustrated as done opposite. The Local Self-governance Act of 1999, which is still the main legal framework, defines three main local bodies: the DDCs, the VDCs, and the local bodies in the bigger district towns, the municipalities.

Let’s take a quick look at the local bodies one at a time. True enough, the DDCs, the VDCs and the municipalities have been dissolved since 2002 and are still formally left in the hands of local civil servants. Local elections have not been held since 1997! But let’s still begin with what the law says.

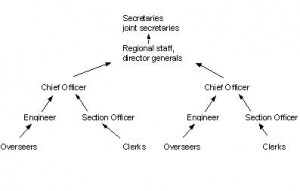

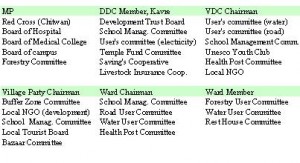

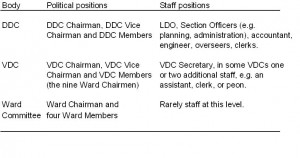

DDCs – or District Development Committees – are located in the district towns. The photo opposite shows a DDC office, in Chitwan. Most offices are less glamorous, but that varies. A DDC is the local government of the district as a whole and typically has ten to fifteen members. They include:

The DDC Chairman, the Vice Chairman, and the DDC Members (also called Ilaka Chairmen).

VDCs – or Village Development Committees – are located in the main village in the VDC. In fact, some VDC’s don’t even have an office but meet typically at the headmaster’s office or at the home of the chairman. The VDC is the local government at village level and always has eleven members:

The VDC Chairman, the Vice Chairman, and nine ordinary VDC Members.

The ordinary VDC Members are also called Ward Chairmen because they each chair a local body in their ward: a Ward Committee. This committee includes another four members: the Ward Members.

Municipalities mainly belong to the towns. To limit ourselves, we’ll say less about them. But they are set up like a VDC, only the titles are Mayor, Vice-Mayor, and ordinary municipality members. Moreover, the subdivisions of the municipalities are locally known, not as wards, but as “tole”.

The local governments are of course comprised of more than just the politicians. There is also an administrative staff, although especially in the VDCs it is quite limited. The following is typical:

A DDC has a Local Development Officer (LDO) who is the director of the DDC administration. He and most other of the staff, such as the engineer and the planning officer, are deputed by Ministry of Local Development. Some DDCs, though, employ additional staff or have staff funded by donors.

A DDC has a Local Development Officer (LDO) who is the director of the DDC administration. He and most other of the staff, such as the engineer and the planning officer, are deputed by Ministry of Local Development. Some DDCs, though, employ additional staff or have staff funded by donors.

A VDC has a VDC Secretary, and the VDC secretary is also deputed by the Ministry of Local Development. Some VDCs employ one or two additional staff on the basis of their own funds. The typical political and administrative positions in the DDCs and VDCs are summed up above.

Local Party Branches

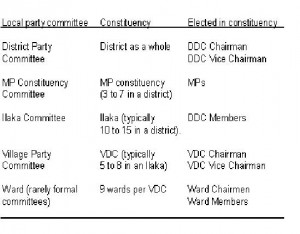

The organisational set-up of local party branches is the same across most parties at an overall level. There are differences in the details, such as meeting procedures and the like. But the formal structure of local party committees under the Central Party Committees in Kathmandu is the same.

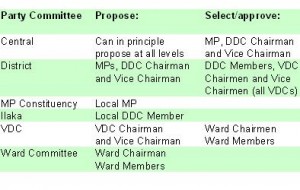

The political parties in Nepal have a set up of local party committees at levels corresponding with the levels of local government and the main constituencies. Let’s briefly list the constituencies.

The biggest constituency is the district itself. This is where the DDC Chairman and Vice Chairman are elected. A district is in turn subdivided into a handful of parliamentary constituencies; a bigger number of “Ilakas” in which the DDC Members are elected; and finally the VDCs and the wards.

The parties don’t have formal committees at all levels. But they all have the following two:

District Party Committees at the level of the DDC and the constituency of the district as a whole. You might not find a district party office, but the bigger parties usually rent a house, flat or room.

District Party Committees at the level of the DDC and the constituency of the district as a whole. You might not find a district party office, but the bigger parties usually rent a house, flat or room.

Village Party Committees at the level of the VDCs and the wider constituency of the VDC. Not least at this level, you’ll rarely find an actual party office. Some local parties simply meet at home.

Two additional party committees are organised by some parties at the intermediary levels. These include “MP Constituency Committees” and “Ilaka Committees”, set up in parallel with the two corresponding constituencies. In many cases, though, these committees are only active in elections.

Chapter 2: Actors and Players in Local Politics

Who are the actors or “players” in local politics in Nepal? Well, there are quite a few. We’ll leave some of them for later. But a set of main categories are good to put on the “map” from the outset.

The Local Politicians

We’ll start with the local politicians themselves. They include, in our sense of the term, all those who strive with more or less ambition to be or stay members of the local governments and/or local party branches. Some politicians are independent, but most belong either to one party or the other.

The social background of Nepal’s local politicians varies. But many people feel that the local politicians – though less than the national politicians – are not representative of the people as a whole. To some extent that’s true. Many local politicians are, say, better off than most villagers.

Indeed, it is a general pattern that the local politicians, especially at and above the level of VDC Chairman, belong to the more privileged groups of the local community. The typical local politician is a middle-aged man, fairly well educated and well-off (but not necessarily rich), and a high caste.

This does not mean that women, for example, are not represented at all. But women are rare above the level of Ward Member, even among the Village Party members. In the same way, politicians from a poor ethnic or lower caste background, and also the less educated, are rare above VDC level.

Why local politicians are recruited mainly from the better off segments of the community is a complex issue. It has to do with the money and time required to be in politics: not everybody can afford it. But it’s also a result of whom voters support and other things. We’ll look at that later.

How many are the local politicians? Well, out of the total population in a district, very few. Take any district or VDC and they’ll constitute a small minority. Of course, the number of DDC and VDC members is extremely limited compared to the population, and so is the active party members.

It’s relevant to make a distinction here between active and general party members. The active members typically work for the party both in and between elections. They are the “party workers”. The general members, in contrast, are only occasionally or never active. They are just supporters.

The table opposite illustrates how varied the number of members in a political party can be at VDC level. It lists the number of active and general members in different Village Party Committees in VDCs with 2,000 to 10,000 inhabitants. In most local party branches you’ll find similar numbers.

The number of active members in a District Party Committee also includes only a small part of the local population. The committee typically counts two or three dozen members. It’s nevertheless this relatively small group of people – the local politicians – whom many locals expect so much from.

Townsmen and Villagers

Local politicians are directly confronted with the locals that are affected by their actions. In fact, it’s difficult for many local politicians to walk down the district town or trough the VDC without being greeted or confronted by people who know them. Townsmen and villagers will often address them.

It’s relevant in a crash course on local politics in Nepal also to have an image of who the locals are. It is common to talk about the politicians, on one side of the counter, and the people on the other, and to insist that that the “politicians” ought to serve the “people”. But who are the people actually?

The people are of course not just a grey mass but a mix of all kinds of demographic and socio-economic segments. Moreover, they make up a patchwork of more or less visible cultural groups. We are here thinking of the different castes and ethnic groups that the population are divided into.

Outside the district town, the far majority of the people are farmers, if that’s not too big a word. Some would rather use the term peasants. Most of the farmers till merely half a hectare or so of land! Of course, the average acreage in a district varies across the country, but few own more.

Villagers, though, are not all small-scale farmers – or peasants – who are able to merely till for their own subsistence. There are also a few big farmers who own many hectares: farmers with access to irrigation and who harvest twice a year, tilling enough to make their farm into a veritable business.

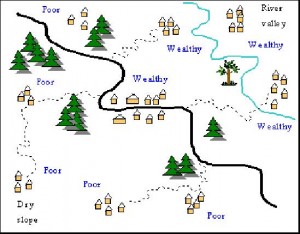

Opposite is a sketch of a VDC which illustrates where you’ll often find rich and poor in a VDC in the Hills. The big farmers typically live in the valleys along the rivers, while the poor peasants reside on the dry slopes. Shop-owners and other wealthy villagers usually stay in the main village.

How much crops the land can yield varies across a VDC. It is inevitable, in turn, that those villages located where the land is rich and irrigable are better off than those situated where the land is less fertile. In the Terai, the poorest villages are sometimes those on the banks of flood-prone rivers.

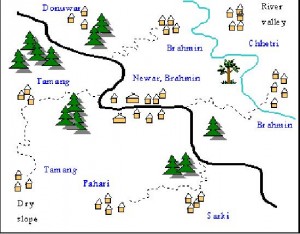

This geographical pattern between rich and poor villages often has a cultural layer. The wealthiest villages are typically inhabited by high castes or other historically (and locally) privileged groups, such as Newars or Yadavs, while ethnic groups and low castes predominate in the poor villages.

The sketch opposite illustrates this pattern in the VDC just depicted. See how the rich villages are inhabited by Brahmins and Chhetris and the main village mainly by Newar (shop-owners) while the Tamangs and Paharis, Sarkis and Donuwars, live in the poor villages? This is a typical pattern.

This does not mean, though, that all high castes are rich and all the lower castes and ethnic groups are poor. In fact, we have met many Brahmin households that were just as poor as ethnic and lower caste households often are, and vice versa. But the overall picture typically is as it’s now shown.

The People in a District

Take anything from thirty to eighty or more VDCs, put them next to each other in some cluster, and you’ll have an image of the settlements in a district outside the district towns: villages that are located some near to the towns and others remote and some in better off and others in poorer areas.

The castes and ethnic groups can be even more diverse once you scale up and look at a district as a whole. Meanwhile, the geographical and cultural pattern between rich and poor is in principle the same. It’s true that remittances has affected this pattern, but on the whole it is still very prominent.

The level of education varies according to this general pattern, too. On the whole, the literacy rate in Nepal’s districts varies from around 30 percent up to around 70 percent, and the highest level of education is in the better off high caste villages while the lowest is in the poorest low-caste villages.

Most locals are peasants but in any VDC you’ll also find other traditional occupations. There will be retailers and teashops, typically a carpenter and a black-smith, perhaps a bike-mechanic, a tailor and shoemaker, and a guesthouse owner, as well as porters, to name the most common trades.

More innovative sectors are also found: entrepreneurs who have entered more novel businesses. Take local transportation businesses, as one example, and local cottage industries such as home moulding of concrete elements for house construction or manufacturing of candy, as another.

In the district town, politicians are faced with locals in a range of additional occupations. There are administrative staff working at the ministries’ local branch offices – the line agencies – as well as contractors and a diversity of other businessmen, and in many districts people working with NGOs.

Teachers, health workers, and policemen are the biggest categories of field personnel. Indeed, it’s staffers in these categories that villagers come into contact with the most. Who do the politicians, in turn, interact with? Well, it varies a lot. But it’s useful to have a look at some of the main actors.

Line agency staffers

The line agencies are extensions of the ministries, and just like the DDC office they are typically located in the district town. It varies between districts how many ministries are represented. But there usually is a line agency for all the development-oriented ministries like education and health.

The districts we know of have line agencies for at least the following sectors: education and health, agriculture and livestock, electricity and water resource, tele-communication, roads and transportation, as well as a land registration office and the CDO’s office under the Home Ministry.

The line agencies are typically smaller offices – each usually with its own building – comprised of one or two dozen office staff and a variable number of field staff. They actually have only limited formal autonomy: they can’t decide much on their own, but have to do what the ministry instructs.

In practice, however, that’s only true to a certain extent. Even the head of a line agency – called the Chief Officer – is not allowed to change much in the plans and budgets without prior approval from the ministry. There is little discretion. But informally, some Chief Officers quite often do it anyway.

The biggest source of funding in a district for development purposes next to the DDC or perhaps a donor-funded local NGO are the line agencies. If you’re a local and want more money for schools or the local health post, electricity lines or a water intake, roads or bridges, this is the place to go.

It’s also true, though, that line agencies – like most other offices in Nepal – are typically under-funded. A line agency has a general budget that covers rent, salaries, and other basic operational costs, and then a development budget for the actual activities. Very often, the latter is very small.

Moreover, even if a line agency has a big development budget, it’s not always easy to get a share. There’s an element of politics involved. You’ll know just by watching the daily activity at a line agency: many local politicians go there. We’ll say more about the political role of the staffers later.

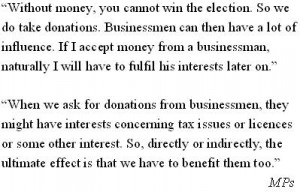

Contractors and Other Businesses

Contractors are another important category of actors on the “stage” of local politics. They are comprised of local businessmen who work on contract both for private and government customers. There are A, B and C contractors defined according to the size of contracts they are licensed to take.

DDCs, line agencies, sometimes even VDCs, hold public tenders in which the local contractors bid. Most of these contracts are either for road tax collection or various public works. In fact, for many contractors it’s crucial to their economic survival to win at least one or two of these tenders a year.

In some districts, many contractors are members of a local Contractor’s Associations. The purpose is not only, say, to discuss common issues or exchange experiences, but also to arrange bids so that each contractor will be able to win at least one tender a year. In that sense some work like a cartel.

The formal system of tender selection is Nepal is the same as in many other countries. Basically, it’s required that the tender is publicly announced and the tender submission date is fixed well in advance, and also that the bids are assessed according to objective criteria. That’s as it should be.

However, it is common that informal links and connections also play a role in determining who gets the contracts. Competition is tough – there are many contractors and few contracts to win – and in order to gain over the others, many contractors are seen to enter the stage of local politics as well.

Other types of businessmen do it too. What kind of political game is it, more exactly? Well, it’s common for contractors as well as other businessmen – from traders to hotel owners – to seek and use links and connections within the political parties as well as the bureaucracy. We’ll see that later.

NGOs

NGOs (non-governmental organisations) mushroomed in Nepal in the 1990s and today there are thousands. Many NGOs have local branches just as there are purely local NGOs. Some local NGOs have a lot of resources due to donor support while others have much less funding at their disposal.

It is well-known that NGOs in Nepal are often associated with political parties. Indeed, in many of the VDCs we have visited over the years it’s common to talk about, say, “NC-NGOs” and “UML-NGOs”. The meaning simply is that some NGOs favour one party and other NGOs favour another.

NGOs have often been labelled core members of “civil society” – a sector which western thinkers have liked to imagine as a sphere being separate from “politics” and “government”. But of course, in Nepal (and in so many other countries) it is not. Many NGOs are prominent players in politics.

Local NGOs also have a portfolio of local groups in many cases through which they carry out their activities. It could be savings groups, women’s groups, or farmer’s groups, or some other category. Such groups have sometimes enabled less privileged villagers to improve their skills and livelihood.

But it’s also true that party-affiliated NGOs have mobilised groups at village level with political intentions. Indeed, just imagine how useful an array of local savings groups can be if distributed throughout a district. Come the election, for example, and they can all be mobilised to help win it.

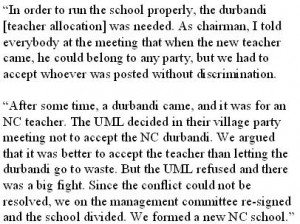

Schools and Student Unions

Schools have been part of the political game in Nepal too for many years. Indeed, under the resistance against the Panchayat System from the 1960s to the 1980s, teachers and the students they mobilised played a central role in generating support against the regime. They were at the front line.

In the 1990s politics continued to play a role at many schools and it often still does today. We have visited VDCs where locals even know the local schools by a party colour. One school would be “NC” and another, say, “UML”. What does this mean exactly? Well, the teachers support a party!

Parties who enjoy the support of teachers in their constituencies have a great advantage. First of all, it’s well-known that teachers can influence their pupils. We have visited VDCs where some felt that the high-school was nothing less than a political playground and a base for recruiting young cadres.

Student unions with party affiliations indeed exist on many high schools and recruitment of young students happens trough them down to grade 7 or 8. Is that unusual, though: to see young people at schools joining a student union and developing political identity? Not exactly. It happens all over.

However, it’s not in all countries that students are that young when they join, nor that schools are known by a party colour. Indeed, we’re not talking about all schools in Nepal, let alone all teachers and students. Moreover, the intensity of the political activities vary over time. But schools matter.

The most unlikely organisations, such as high-schools as we have now seen, can be entangled in the game of local politics. More organisations could easily be added to the list. Take user committees, dairy cooperatives, or insurance funds, even local temple committees, and you’ll often be surprised!

Chapter 3: Needs and Interests

What are the needs of the people of Nepal? Many would promptly answer: “development”! Or they would say “democracy” because only with “democracy” can we ever achieve “development”, or something like that. Indeed, this is not wrong: since so many people will say this, it’s clearly a need.

But it’s also clear that needs in a district can be very diverse. Just go to any VDC and visit any two wards within it. Chances are that in one ward, they’ll ask for a school or electricity lines, while in the other their biggest need is, say, a water intake or a better road. Rarely will the need be the same.

Why is that the case, one could wonder, since two wards could just as well have the same needs and pursue those needs together? After all, if located near each other, they could have their main needs in common. Well, they sometimes do. But often, the most urgent need is specific to the locality.

The needs in Nepal’s districts and VDCs are to a large extent geographically determined. In a way it’s only natural. Villagers mostly stay in the same place for years – in the village – and their needs are typically about services and infrastructure, resources and opportunities, in their own community.

That’s not to say that everybody will always prioritise the same need even within the same ward. Just think of the household who has a young son looking for a job? It’s not difficult to imagine what they might be looking for. Or consider the household whose children are still going to school.

However, there will very often be a need which most villagers share, and it will often vary from one ward to another. Indeed, it will also vary greatly from VDC to VDC. One VDC may mainly need a road or electricity, another may put school renovation on top of the list, maybe a third a health post.

In other words, the politicians will be faced with many different needs across different VDCs. In the district town, the same pattern will typically apply as you visit the different neighbourhoods or tole.

We will call this the “geographical aspect” of people’s needs, and it plays a big role in local politics. There is also the “individual aspect” of people’s needs. Like everywhere else, there are groups and individuals with their own needs. Just think of the contractor who might need help to get a contract!

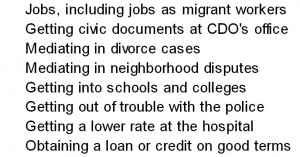

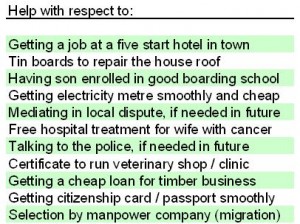

It is, in fact, difficult to delineate the type of needs that politicians in Nepal can be presented with. Foreigners who think of politics as a field of “public debate” and “elections” are often surprised by it. Locals will ask politicians for help in almost any matter. Just check out the list of needs opposite.

We once made a survey and almost everybody said it was common to ask a politician for a job or help in a neighbourhood conflict. If you can’t cover the bill at the hospital or are in trouble with the police, you typically ask a politician for help too, if you have the opportunity. The list just goes on.

Chapter 4: Values and Norms

What values and norms ought to regulate the game of local politics in Nepal (and politics at the central level for that matter)? Many would immediately cite values and norms associated with “development” and “democracy”, such as equality, the common interest, accountability, and so on.

Ask anybody and they’ll usually say that in the overall the politicians ought to serve the “people” as a whole. Many would add, in combination with this overall value, a wish that the politicians would especially focus on those most in need: the “poor” and “excluded”, “landless” and “low castes”.

Many locals will insist that the politicians should act, not like “politicians” who always “struggle for power”, but instead like “social workers” who will serve anybody in need. You’ll often hear that term out in the districts and villages: to be a “social worker” is often considered a value of its own.

It’s common to say that the politicians must follow “democratic” values and norms. Many will say that “democracy” is a value, urging the politicians to respect the requisite “democratic” norms. In short, it’s common to voice support for values and norms associated with western societal models.

Values and Norms Linked to Family and Friends

It’s also well-known, however, that values and norms rooted in people’s closest relationships often mean just as much or even more. In fact, it’s impossible to understand local politics in Nepal without being familiar with these values and norms. The first that many mention is “afno manche”.

“Afno manche” is not anything mysterious or even unusual. You’ll find something like it in many other countries, not least in the less “developed” parts of the world. Afno manche means “one’s own people” and it refers to the circle of family, relatives and friends with whom you are “close”.

It’s not enough to have a blood relationship. After all, there could be an uncle who doesn’t really care about you. “Close” hear refers to a relationship that involves a mutual feeling of loyalty and obligation. Typically, though, this type of feeling is strongest among family and close relatives.

The status and well-being of the family and other associates is a value, and the corresponding norm is to help one another. The family – not just mum and dad, uncles and cousins, but also the extended family – is simply of great importance. The norm of helping one another therefore plays a big role.

What is that norm, more precisely? In short, it is to help your relatives and friends if you can, and to be able to expect that they’ll help you in return, when you’re in trouble and need to resort to your “own people”. In a society with little social welfare by the government, this is a crucial relationship!

Values and Norms Linked to “Big People”

It’s critical that we include another set of old values and norms in this crash course too. Imagine if your relatives or friends simply lack the resources or the position to help you in a certain matter. What would you do? Well, what’s common to do in Nepal is to try and approach a “thulo manche”.

The term thulo manche means “big people” in the sense: wealthier, more powerful or influential than you. It’s someone who can solve problems for others based on a position at a higher level. It’s common to consider not least a powerful politician a thulo manche. So, you approach such a person.

It’s an age-old practice in Nepal, moreover, to attempt to develop good relations with big people. If you think the local VDC Chairman, the landlord, the MP, perhaps the Chief Officer, or a wealthy businessman in town, could help you with something, it might be good to offer him a service first!

The age-old practice is, in other words, to try to become “close” with big people by offering either a service or something tangible when the opportunity arises, hoping for some reciprocity later on. The practice even has a term. At least, it’s often referred to as “chakari” or, in a lose translation, flattery.

Flattery in this sense is everywhere. Go to any district, visit any office or the home of any powerful politician, and you’ll eventually get a chance to see the behaviour first hand. If you ever see a party worker carrying the MP’s bag, or a junior officer rushing to fetch tea, you’ve had a glimpse of it.

The practice is to nurture a relationship with big people that approximates as closely as possible that among one’s “own people”. Indeed, when a “big man” helped out several times, the less privileged recipient – the “small man” – will often begin to refer to his “patron” as one of his afno manche!

But what’s in it for the big man: the thulo manche? Well, in a common term, he’ll gain “patronage” in the community: he’ll have an array of small people under him who will not only owe favours to him but also have a strong motivation to return those favours. Of course that can be a big advantage.

Values and Norms: More to Consider

We couldn’t even hope to cover all the values and norms that pervade the context of local politics in Nepal. In fact, the game of local politics takes place amidst a huge mix of values and norms. Just think of all the castes and ethnic groups who each have certain values and norms particular to them.

It’s clear by now that a district is comprised of a great plethora of circles of afno manche and of relationships between big people and small people. In our experience, all these circles and relationships can be entangled with each other in so many ways that we could speak of “networks”.

The values and norms that play a role inside these networks, but also outside them, include more than described so far. For example, young people usually hesitate to object to the commands of older ones: young must respect the senior. That’s the norm! The same norm applies in local politics.

It’s a strong aspect of any relations between people of unequal status that one must show respect. Observe subordinates interacting with superiors in any context and it’ll be evident at once: you’ll very rarely hear a subordinate object or even suggest alternative options unless he’s asked directly.

We would be amiss without also adding values and norms in gender relations. Indeed, most local politicians are men. In fact, we have rarely met women in any positions except at the lowest level, in the wards. Is that because women are discriminated against? Well, that’s part of the answer.

One thing is the role men and women are brought up to play in the family and in society, though, another is discrimination. Take the term “sari politics”. It’s well-known in Nepali politics that if you want to influence a powerful politician, go to his home and ask his wife (who wears sari) to talk to him!

It’s even more important to note, we think, that all these values and norms about showing respect – between young and old, subordinates and superiors, men and women – vary between families and other relationships. Moreover – slowly – change is clearly taking place in many values and norms.

But why look at all these values and norms? Well, what is customary or the “right thing to do” can play a big role – though it not always does – in decision-making and everyday interaction in local politics: who politicians serve or favour, who they listen to, who is obeyed – can be affected by it.

Chapter 5: Capacity and Power of Local Governments

The local parties are all urged to use the capacity and power of the local governments to serve the people as a whole. That’s a major public demand. Ask anybody, and most will reply on a general level that the local politicians ought to use their power to make “development” across the district.

But what is the capacity and power of local governments in Nepal to “develop” a whole district: to meet all the needs and interests for roads, electricity, drinking water, schools, health posts, and so on? Well, we’ll have to distinguish here between two periods: before and after the fall of 2002.

Capacity and Power of Elected Local Governments

Up until 2002, which was a year when not only local governments but also parliament itself were dissolved and replaced with appointed officials, their capacity and power did increase. In fact, much was achieved in the area of “devolution”: the transfer of power and resources to the local level.

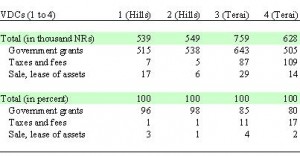

A UML-led government took the first step in 1994 as it raised the annual block-grant for the VDCs from less than 1 to 3 lakh. One year later, the successive NC government trumped this gesture by raising the amount to 5 lakh or 500,000 rupees. Also the DDC grants were raised during this period.

In addition to that, and strongly promoted by donor agencies, the Local Authorities Act was replaced with the Local Self-governance Act. This act gave the DDCs and VDCs certain further powers, including powers to collect more taxes and to organise committees to carry out the work.

However, the DDCs and VDCs remained left not least with grossly inadequate financial capacity to effectively handle the responsibilities assigned to them and to meet local needs and expectations. Indeed, the 5 lakh to the VDCs was a major improvement. But in a whole VDC it’s a small amount.

5 lakh is enough to build a couple of average size classrooms and pave a stretch of road. However, if what you want is to provide services and infrastructure in all the nine wards in a VDC, and if you’re also trying to make bigger infrastructure like a high-school or a health post, it is inadequate.

As a result, it often takes several years to complete a bigger project in a VDC simply because the 5 lakh will only cover part of it. Take a school building. One year the VDC will do the walls and part of the roof; the next put in furniture and start teaching; and the third year maybe install the toilets.

It’s true that a strengthening of the fiscal powers of the local governments occurred. The Local Self-governance Act gave the DDCs and VDCs authority to raise and keep more and new types of local revenue. But on the whole, local revenue, especially at VDC level, has remained quite limited.

The DDCs collect revenue mainly from road tax and extraction of raw materials on DDC land. In most cases, contractors are given the tasks and pay a percentage of the revenues back to the DDC. VDCs mainly collect land tax. But due to a small tax base in many areas, local revenues are small.

In sum, most DDCs and VDCs lack the financial resources to effectively meet the numerous and typically basic needs in their areas: needs such as more classrooms, health posts, teachers and medicine, electricity and drinking water, and much more. Every year many needs are left unmet!

Grossly Inadequate: Staff Capacity

It’s not only the financial resources that are inadequate. So is the staff. Some DDCs and a few VDCs have the funds to employ staff. But most staff is posted by and under the Ministry of Local Development. Some DDCs have hired, say, a few project officers, but otherwise it’s very limited.

It requires much time, as well as vehicles, fuel, and manpower, for a DDC to cover the district as a whole. A DDC administration is supposed to frequently go to the VDCs and inspect ongoing projects, evaluate the work done, supervise and monitor. However, most lack the capacity to do so.

A DDC would usually have one engineer, two or three overseers, and perhaps a few sub-overseers, all deputed by Ministry of Local Development. That’s it for technical staff. Indeed, if they all work at full intensity, perhaps they might be able to cover a large chunk of the district. But they rarely do.

To cover the whole district requires not only staff but also vehicles and fuel. DDCs often lack both in adequate quantities. If three overseers have to share one motorbike, and if the budget is not enough to fill the tank every day, well, covering the whole district is bound to take a lot of time.

VDCs usually don’t have technical staff and must go to the DDC in order to obtain assistance, simply because they lack funds to employ their own. There are many good reasons why the VDCs are not given funds to cover expenses like staff salaries. But the fact is that it limits VDC capacity.

Capacity and Power after 2002

The issue of capacity is essentially the same today as prior to 2002. Of course, a lot has happened in between. The king – Gyenendra – stepped down after a failed attempt (or whatever it was) to take power, and a general election for a Constituent Assembly was held in 2008 which the Maoists won.

The 2008 general election was indeed followed by a perhaps surprising decision to postpone the local elections. It was decided to set up so-called “All-party Committees” instead each reflecting the composition of the Constituent Assembly. But these committees were dissolved in January 2012.

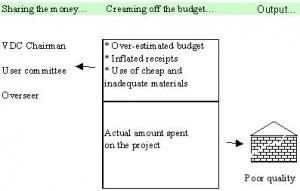

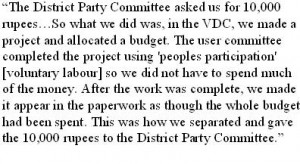

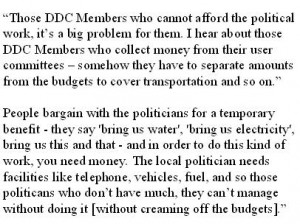

Politicians in the all-party committees engaged in corruption. They colluded internally and possibly even with LDOs and VDC secretaries to misuse local budgets and other resources. In the media, it was portrayed as a free-for-all. Somehow, the all-party committees had been able to gain influence.

The LDOs and the VDC secretaries had been in charge of the DDCs and VDCs since the kings’ coup in 2002. They still were and the all-party committees were only supposed to act as a kind of advisory bodies. The local politicians involved in them, however, engaged in much more than that.

Many observers in Kathmandu felt that local corruption had grown out of control and applauded the Minister of Local Development when he followed a CIAA recommendation and dissolved the all-party committees. Indeed, the all party committees remain dissolved also at the time of writing.

It’s true that more resources are now available to the local governments. In 2011, the government made an additional 5 lakh available to each VDC. However, the VDCs must apply to the local LDO for this grant – project by project. So, as a self-governing body, the VDCs still only have 5 lakh.

The DDC grants have also been enlarged in recent years, but mainly in the form of donor funds. The DDCs must often apply for these funds and much of it is earmarked for specific sectors or purposes. So, the power of the DDCs to use many of these grants is also attached with conditions.

Chapter 6: Serving the People: Development Work

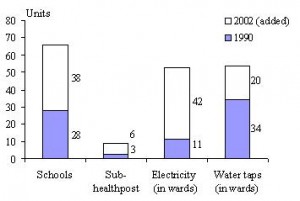

The DDCs and VDCs have made a lot “development work” despite the lack of budget and staff. What is “a lot”? Well, the local achievements vary, but in many districts and VDCs they have at least provided many more services and infrastructure after 1990 than in any previous decade.

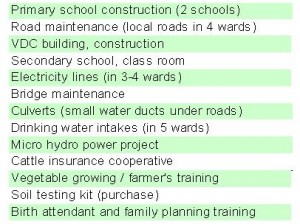

The DDCs and VDCs have planned and implemented development work that have served many people. They have built roads and bridges, schools and health posts, electricity lines and water intakes, river dikes and irrigation canals, and carried out softer activities like farmer’s trainings.

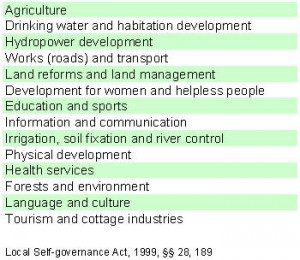

What types of development work have DDCs and VDCs been required to carry out under the law? Well, the Local Self-governance Act lists a whole range of sectors which spans from roads and bridges over education and health to electricity, water resources, and even tourism development!

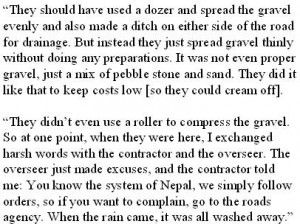

The development work of the DDCs and VDCs in many districts and VDCs is not much relative to the needs of the people. However, it would be wrong to say, as some do, that the local bodies have not provided any development at all. Despite the lack of capacity, and despite misuse of resources, quite a lot of work has been done.

In all DDCs and VDCs that we have visited, at least, local records and field observations clearly show that a significant amount of development work has been done. The list opposite is just one example. It shows the variety of development work carried out in one VDC over a five-year period.

In 2002 – the year elected local governments were dissolved – we visited a number of VDCs to look at their achievements: how many roads, schools, health posts, electricity lines and water intakes had been built since “democracy” began in 1990. In these VDCs, quite a lot was done, as shown left.

It’s also true that some DDCs and VDCs have done much less. Indeed, it varies. Moreover, line agencies, NGOs, and donors implementing programmes directly in the community, also account for many of the achievements. But many local bodies have provided more development than earlier.

Chapter 7: Favouritism in the Distribution of Development

Have the people as a whole benefited from the development work or only some sections of the local community? In many areas, some groups and people have clearly benefited more than others. This is a well-known and much criticised aspect of local government. Favouritism plays a very big role.

In fact, the Local Self-governance Act requires the DDCs and VDCs to serve the local people as a whole and only to give special attention to less privileged groups. They must give priority notably to ethnic groups and lower castes, landless and the unemployed, and to women, children and elders.

Time and again, however, the power-holders in the DDCs and VDCs have favoured other groups instead. Indeed, go to any district or VDC, even to the most “developed” ones, and you’ll often find a quite skewed distribution in favour of groups and people that are not among the least privileged.

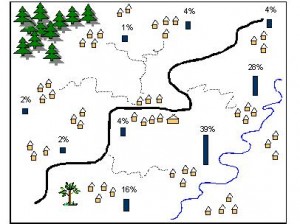

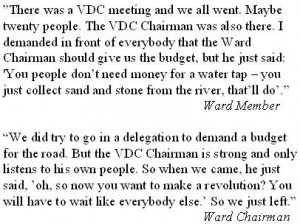

Just look at the example opposite from a VDC that we once visited. Check out the distribution of the 5 lakh on development work meant for individual wards over a five-year period. It’s readily clear that in this VDC, there was a tendency to favour two or three wards.

Were the favoured wards in this VDC the “poorest” or most “marginalized”? Far from it. One of the wards was even the wealthiest, located by the river where the big landlords lived. The other wards were under the leadership of Ward Chairmen who were, in a term, “close” to the VDC Chairman.

There are also cases in which areas where the least privileged live were favoured. The illustration opposite shows the case of three wards inhabited by Tamangs – a generally less privileged ethnic group in the Hills. But two other wards were almost just as poor in this VDC and yet largely ignored in the allocation of the budget.

So, roads are gravelled and classrooms are built, health posts are constructed and electricity lines set up. But the power-holders in the DDCs and VDCs far from always decide who should benefit based on the objective criteria in the law. Frequently, it is more informal, political considerations that weigh more.

Who is favoured

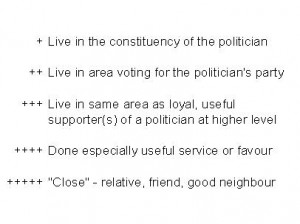

It’s well-known that local politicians (like many national politicians) to some extent tend to favour their “own people”: their afno manche. DDC Members do more work, say, for their own VDC, VDC Chairmen do more for their own ward, and Ward Chairmen do more for their own village.

But favouritism is more complex than that with respect to the categories of favoured people. There is a term in Nepali politics called “area politics” or: politics focused on the constituency. Indeed, a very common proclivity among local politicians is, first of all, to favour their own constituency.

Moreover, it’s also typical not to serve everybody in the constituency to the same degree. In any constituency, locals will tell you that some areas are, say, “NC” and others “UML”, meaning that different areas are supportive of different parties, and the politicians tend to favour their areas more.

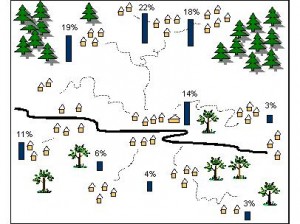

Does this mean, though, that you’ll get a lot of development work to your area just as long as the party you support is in power? Far from always. Chances are better but you might be set aside in favour of areas in which the most loyal and useful supporters of politicians at higher levels reside.

MPs, DDC Members, and other politicians at higher levels, have a tendency to favour those areas in which local supporters able to promote their interests locally live. In short, they’ll favour a local politician who always looks after their interest – e.g. local electoral support – in his particular area.

Businessmen, civil servants, and many other individuals who have, for instance, donated money to the politician, or done some other especially useful service, are another favoured category. The nature of the benefits they receive, however, is rarely development work, as we’ll see further below.

It’s also true, though, that family and friends are usually favoured the most: it’s where the politicians and his closest “afno manche” live that the largest share of the development budget is often spent. Indeed, there are exceptions. But it is common to find a skewed distribution in favour of the “closest” ones.

Chapter 8: Decision-making at Formal Meetings

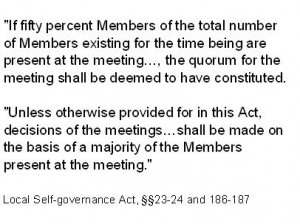

How is it possible for the politicians in majority in a DDC or VDC to channel the biggest share of the budget for development to their supporters – and to do so following a norm of favouritism rather than the formal criteria spelled out in the Local Self-governance Act? Well, the answer requires a look at formal meetings.

The DDCs and VDCs – prior to their dissolution as elected local bodies – were typically comprised of politicians from at least two parties, often three and even four. In the 1990s, NC or UML were in majority in most DDCs and VDCs. Today, if local elections were held, it might be different parties.

The elected DDC and VDC members from the different parties must hold two types of formal meetings. One type is monthly DDC and VDC meetings to discuss current matters while the other type takes place once or twice a year – a District Council and Village Council meeting – above all to make the budget.

The Local Self-governance Act stipulates, in turn, that the decisions are to be made on the basis of a simple majority vote. So, in short, the party in majority (or sometimes two parties in coalition) has the formal and legal prerogative to make all the decisions at the formal meetings.

The result of this decision-making rule is as follows: since in many DDCs and VDCs one party sits on more than fifty percent of the seats, one party also makes all the decisions. The law entitles it to do so! Or when more parties are represented, a two-party coalition dominates.

Just take one example from a Village Council meeting in a VDC in Kavre. You can read it here in detail – and it’s just one of many. The minority – in this case NC – would raise questions and ultimately start to shout in protest. But the majority – here the UML – would still decide the budget.

Does this mean that “debate” and “compromise” never plays a role in the decision-making? Not entirely. Compromise and even cooperation does happen under certain circumstances, as we’ll show later. But on the whole, in the DDCs and VDCs the simple majority rule is often used to the fullest.

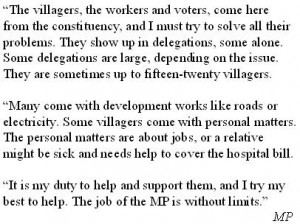

Chapter 9: Serving the People: Personal Benefits

The DDCs and VDCs are legally defined as local government bodies that carry out their activities in a planned and organised manner as coherent bodies. However, until they were dissolved, DDCs and VDCs were in practice comprised of local politicians who indeed each had their own constituencies.

Townsmen and villagers in Nepal typically look to their local politician as a representative, not necessarily of the “party” or the “people” alone, but also of their constituency and themselves as

voters. If you have supported a local politician, even an MP, somehow you expect something back.

Politicians, however, are not only expected by local supporters to provide benefits in the form of development. It’s also common to expect other and more personal benefits. Just look at the list opposite. It shows the type of personal benefits – tangibles and services – that villagers we once asked mentioned.

Townsmen and villagers frequently go to the local politicians in their areas with all kinds of needs. They might need a job for their son – so they’ll ask the politician for help with that; or they might need help in getting a civic document, cover the hospital bill, or get out of trouble with the police.

Politicians at all levels of a district, at least in our experience, frequently spend a lot of time on trying to meet these personal needs. Are they required to do so according to the law? Not at all! But they do it, nevertheless. You’ll often see local politicians on their way somewhere to meet a need.

It’s not everybody who can expect help of this kind. Once again, like in the case of development work, favouritism plays a big role in who gets what. It’s mainly supporters – voters, party workers, especially loyal politicians, contributors, family and friends, and so on – who can expect such help.

But how do the politicians learn about the personal needs of supporters? Well, their supporters go to them and ask for help. Those who are close to a politician from the NC go to him; those who feel like supporters of a UML politician go to him, and if you’re a relative, it’s obvious where you’ll go!

Chapter 10: Elections: How Politicians Win Votes

It’s common to say that voters in a country will support those parties that show commitment to serve the “people”. Elections are won by those who have “performed”! But in Nepal many feel that elections don’t really work like that. Indeed – as this part of the crash course will show – the politicians win votes in diverse ways.

Many people would in principle like power-holders to serve the “common interest”: to do what’s ultimately best for everybody. If the politicians we elect prove to care little about the “people” in practice, then we hold them accountable in the next election. Fair and simple isn’t it!

But it’s also true that the way voters vote is more complicated than that – also in Nepal. Indeed, it’s not least when you look at elections that it’s good to bear in mind that the “people” are not a uniform mass. They consist of many segments and groups whose interests differ.

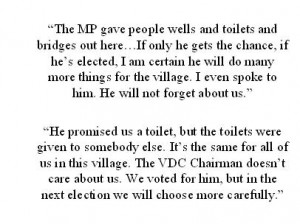

Many voters in Nepal feel discontent when the politicians promise one thing only to do another: when the politicians they voted for promised to serve the whole VDC only to favour their own ward; or when they pledged to built a school only to spend more time on getting someone a job.

But at the same time, those voters who benefited typically praise the very same politicians and even consider voting for them again! In fact, while politicians who do not serve the “people” in the wider area, or in their constituency as a whole, face criticism from those voters they neglected, they often receive support from the voters they served.

Political parties in any country represent different interests in society, however broad or narrow those interests might be. Take the old social-democratic parties of Europe: they represented the interests of the “working class” – conservative parties those of the “wealthy”.

In contrast, parties in Nepal are not based on the support of wider socio-economic segments. Go to any VDC and you’ll find that some “poor villagers” support one party, some another, and still some a third. How is that possible? Well, “poor villagers” are just not tied up with any single party. They vote for different parties and alternate too.

Politicians in Nepal face voters whose interests are typically not linked mainly to a wider segment in society, such as the “working class” or the “poor villagers”, but to their locality. Sure it’s nice if everybody gets a school, but many voters need it in their village first! In short, the politicians have to win votes village by village. How is it done? Well, let’s look at some of the main methods.

Election Campaign Methods

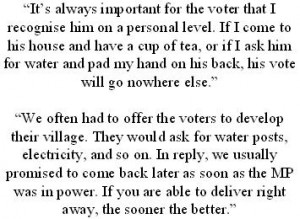

Politicians in Nepal often promise to meet the “need of the village” – that’s one common campaign method. We have met many local politicians who have told us this, sometimes with regret but always with the explanation that “there is no other way”: whoever promises to meet the need of the village will often win the vote.

Another important method, though, is to make oneself visible in the constituency in between elections. Many politicians say that to win an election, it’s good if you gain a reputation beforehand as a helpful leader – indeed as a social worker – who is approachable.

However, it’s also a common experience that many voters tend to forget earlier performances if a new candidate shows up and delivers weeks before the election. Some politicians will erect a line of electricity poles or gravel a road and locals will vote for this new “big man” in return!

Why don’t the politicians simply promote the party’s official ideology and policy goals? Well, the parties do have official programmes. But since most of the voters know little about ideology, and actually look for much more particular and tangible things, it’s difficult to win votes on that basis alone.

Voters we have talked to in various VDCs typically knew very little about party ideology, even about policy goals. In fact, we once carried out a survey in a number of villages, asking the voters if they knew the difference (ideological or otherwise) between NC and UML. 74 percent didn’t know!

Some voters don’t know whom to vote for whatsoever. They take advice from others known as better informed. Many listen to the local teacher or other “respected persons”; in the ethnic villages, such as the Tamang and Tharu, most vote as the village leader suggests.

Politicians are well aware of this less informed and less confident segment of voters. So they invest a lot of time and resources in trying to win the support of teachers, village leaders, and other “respected persons”, because in that way they might win the votes of those who listen to them.

With other voters, it can be decisive to show that you are one of their “own people”. If you can impress upon a caste or ethnic group, for instance, that you are “their own man”, they’ll support you. It’s also true, though, that voters often give up that support again later if you don’t deliver.

Afno manche and close ties between big people and small people play the biggest role in local elections. More locals will feel “close” to a given candidate than in a general election. At ward level, many politicians will win because many voters were relatives, friends, and good neighbours!

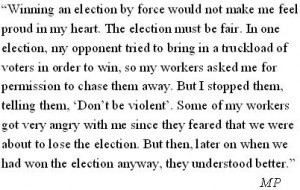

What about “vote buying” – another common campaign method? Indeed, many politicians have told us how regretful they are of vote buying. It’s like raping the people, many say. But it is nonetheless a fact that vote buying occurs. Politicians buy the votes in cash or kind voter by voter or in bulk through electoral middlemen.

Winning a Majority

Politicians in a district or VDC know that to win an election, you need to win the most votes – not all of them – and to be successful in doing that, it’s crucial to be able to alternate between the campaign methods now described. In order to do that, you need to know your constituency and it’s people well. Let’s take an example:

In one VDC we once visited, there were three Tamang wards. The other wards were inhabited by Brahmins, Chhetris and Newars. Three of these wards, located in one end of the VDC, were NC, the other three UML. The two latter areas always competed with each other.

The NC and UML leaders only knew too well the formula for winning the election in the VDC: whoever was able to win the support of the leader in the Tamang wards – the “Tamang leader” – would win the majority of the vote. So, the key was to induce the Tamang leader to support them.

The formula is the same – in principle – in many other VDCs in Nepal. Politicians are conscious of the number of voters in different parts of the constituency, and they consider how those voters can best be mobilised. If it’s enough to win, say, three wards, politicians will try to plan how to do that.

In practice, to do all this is more complicated than it may sound here. To win an election even in a VDC takes knowledge about the constituency and what goes on in it. That’s why MPs and other politicians at higher levels often value – and favour – those locals who can promote them locally.

To win an election in Nepal – whether a general or local election – requires a big effort by local politicians who knows the ins and outs of their constituency and who can turn votes in their favour. How it’s done varies greatly. But let’s just say that on the whole you need to master many campaign methods.

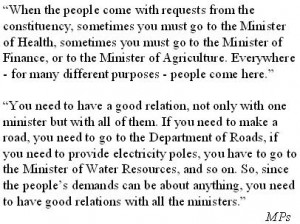

Chapter 11: Accessing Resources to Provide Benefits

Voters and other supporters expect benefits after the election – and in order to respond, the local politicians need resources. Above all, they need budgetary resources. Or else they won’t be able to provide the schools, roads or other services and infrastructure expected in their constituencies.

How do local politicians access budgetary resources? Well, there is a formal system. But many local politicians also make intense use of “links and connections”. In the effort to get a budget, local politicians even use informal channels at central level. But let’s start with a look at the formal system.

How Politicians are Supposed to Get a Budget: Formal Planning

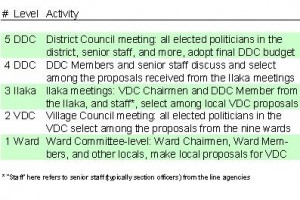

Resources are scarce and so – in the effort to “get a budget” – the local politicians are legally required to follow a formal planning system. This system is somewhat in disarray because of the dissolution of the local governments. But it’s been applied and practiced since the early 1990s.

It’s called the “bottom-up planning system” which refers to the basic principle in it. In five basic steps – from the “bottom up” – the local politicians must collect and prioritise proposals for local development work in their areas. It starts at ward level and ends at district level.

The Ward Chairmen must first collect proposals in their respective wards. They and the other politicians at village level must then decide in each VDC – on the basis of objective criteria – what is most needed. What they cannot fund locally, they must submit to the next level: the Ilaka.

At Ilaka level, DDC Members, VDC Chairmen and line agency staffers must meet to prioritise the proposals of the VDCs. Once again, the selection must be based on what is most needed. But even when a proposal is selected here, it’s at later meetings at DDC level that the final selection is made.

What the DDC prioritises but cannot fund – which is usually a lot of proposals – is submitted to Kathmandu. The budgetary resources even at DDC level are limited, so asking the central level for help is common. The local politicians are then required to simply await the decision from above.

Politicians that we have talked to about the bottom-up planning system agree with it in principle. It makes sense that the local bodies prioritise and submit larger projects to the higher levels, most say.

It’s also well-known and widely admitted among local politicians, however, that the formal planning system is grossly manipulated and bypassed. Politicians attend the formal meetings. In VDCs we have looked at, the attendance rate is typically 75 percent and above. But many don’t stop there.

Informal Means of Accessing Resources: Links and Connections

It’s common to resort to links and connections in the attempt to increase the chances of getting a budget for one’s proposals. If you’re in majority in the local bodies, your position to ensure a budget at least for some proposals is good, as we have seen; if not, using other channels is typical.

It’s important to bear in mind here that the bulk of the state budget is allocated and managed in Kathmandu. The degree of devolution in terms of fiscal transfers remains limited in Nepal. In fact, around 90 percent of the annual budget is reserved the ministries and other offices at central level.Politicians at DDC and VDC level are only too well aware of this division of resources. They know that in order to get a share of the budget – if their formal proposal failed, as many do – ultimately there is only one way: go to Kathmandu. Or, more precisely, use whatever good relations you have in the capital!

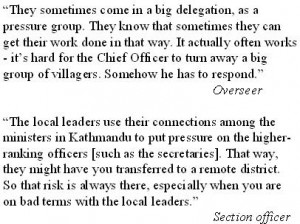

MPs actually face the same problem. If they didn’t become ministers, or got some other influential position, they too often have to convince members of government to consider their constituency. But at least they typically stay in the capital. Local politicians usually have to travel.Go to any district and you’ll see how DDC Members and VDC Chairmen, District and Village Party workers, and a host of other local politicians with the time and money at their hands, take the bus, ride their motorbike, or hitch a hike with a friend, to go on a “lobby trip” to the ministries.

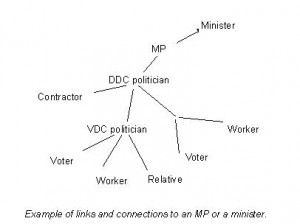

If their local MP became a minister, they will typically have good relations with him already. In that situation, it will usually be easier to convince the minister to set aside a budget for their proposal than if they were strangers. Once again, “afno manche” and being “close” to the big man is crucial.MPs often spend several hours a day on average receiving “workers” from the constituency also after the planning process is officially over. DDC Members and VDC Chairmen, Ward Chairmen and Ward Members, show up alone or in small groups at the MP’s home to present their matters.

It’s also true that local politicians might simply make a phone call. If they know the minister or the MP well – if they are truly “close” – it can be enough to dial up. One DDC Member once told us how he was able to override a line agency decision on teacher recruitment by calling up the minister!

But many local politicians at VDC level lack the links and connections to go to Kathmandu on their own. Indeed, it also takes time and money to make the trip. So, Ward Chairmen and Ward Members often ask the Village Party Chairman, who might ask the DDC Member, to go on their behalf.It works like a vertical network and is known locally as “speaking and listening”: “bhaan-sunn garnu”. If you don’t have a direct channel to the minister or MP in Kathmandu, you first go to the one immediately above you. He will listen and then speak to the one at the next level; and so forth.

Who gets access through the channels of this informal network structure? Well, those who have links and connections. In fact, the network structure – diffuse and at the same time all-penetrating as it is – also entangles the bureaucracy and line agencies under the ministers. We’ll look at that part later.

Motives of the Politicians: Why Use Links and Connections

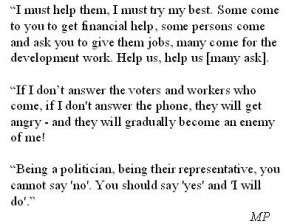

Scarcity of resources calls for careful planning to make the best use of what’s there. So, if the politicians agree with the formal planning system in principle, and with it’s overall purpose, why do they go about manipulating and bypassing it? Politicians we have talked to give various reasons.

One reason is that it’s really difficult to prioritise when all the needs are basic and many equally urgent. How do you decide whether one ward should have a road and another a water intake, or whether one VDC should have a school and another a health post. Many needs are equally acute!Inadequate allocations are another reason. Your proposal might be selected but the budget just not be enough. It’s common only to set aside part of the budget – then you’ll have to raise the rest of the money through other channels or wait until next year – and that motivates bypassing the system too.

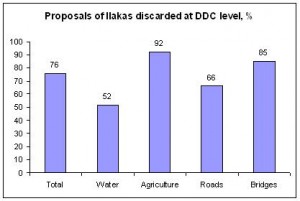

Chances of one’s proposal being selected are small in the first place. Countless of local proposals are discarded every year. We looked at the numbers across four sectors in one district. On average, three out of four proposals selected at Ilaka level were subsequently discarded at DDC level! The inclination to manipulate and bypass the formal system, however, also comes from another front. Many politicians feel that unless they provide benefits to their supporters, they will become unpopular among them and ultimately lose support. To provide benefits, they have to get a budget.Is this just a bad excuse or is the risk of losing support unless you provide at least some benefits a real one? Well, many politicians describe it as very real. So do many party workers and voters. In fact, many voters think of the politician as a “thulo manche” who should help them back in return.

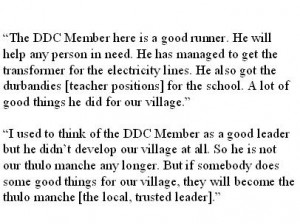

Locals often praise those local politicians that they see going to Kathmandu again and again and returning with benefits for them and their locality. Those politicians who appear to go to the higher levels in an unrelenting effort to access resources are known as “dhaune manche” or: the “runners”.Those who don’t go, and who therefore seem not to care about the needs of their supporters, are typically unpopular. If they are seen occasionally to help someone any way, they’ll be known as politicians favouring their “own people” while neglecting everybody else. Here are some examples.

Chapter 12: What Drives Local Politicians

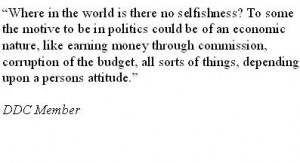

The question of motives naturally comes up in a crash course on local politics in Nepal. It’s often raised – and answered – in the public debate too. What motivates the local politicians? Well, many would say “power” and “money”. But what then, say, about the eagerness to be local runners?

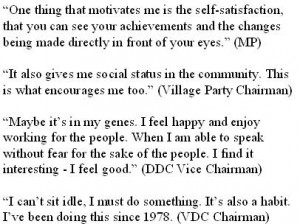

But many also state other motives. Above all, many local politicians actually claim to enjoy doing this type of work. They like the social aspect of being an active local politician who is meeting with high and low, and many get a “good feeling” at seeing the results of their work in the community.

It’s even a career for some local politicians – a path in life – that has become a “habit” in a sense. Local politicians – like many national politicians – have often started out in politics at a young age, motivated to make a difference in their community, but also attracted by the excitement of politics.Ask a politician in any other country and they’ll give you very similar motives. They want to live up to their promises and thus to serve the people who support them. They want to be the one’s who are known to solve people’s problems, just as they also enjoy the work and the results it produces.

Costs of Being a Politician: Time and Money

Local politicians in Nepal, however, have to be so motivated that they are also willing to spend a great deal of their time and money on politics. Of course, politics will always require participating in meetings and such. But, if ambitious, a local politician must be ready to do much more than that.

People will come at any time and ask for help, as we have seen, and if you say no too many times, they will start to speak badly of you. A delegation will ask for help to get electricity to their ward; a neighbour will request help to find a job; somebody will need help to get a passport; and so on.

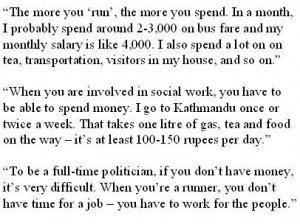

It’s not without costs, in turn, to be a “runner” that has to go to the higher levels in order to meet all these needs. Local politicians that we have met describe it as costly. Usually, the individual politician receives no financial support from the party. You’ll have to cover the costs yourself!Politicians elected for the local bodies get a small meeting allowance. That amount covers meeting expenses – such as getting to the meeting, buying tea and snack while away, and so on – but it doesn’t go a long way in covering all the other expenses incurred as a “runner” who has to travel.

It costs money to take the bus to the district town and Kathmandu. Getting around in the capital does too. Filling the motorbike to drive out to the villages can be equally expensive. In addition, DDC Members, in particular, must sometimes host village politicians on their way to Kathmandu.The time required for politics takes time away from income-generating work. Ward Chairmen and Ward Members, whose constituencies are small, still have plenty of time for the farm or their local business. But go to the level of the VDC Chairman or Village Party Chairman and it becomes busy.

DDC Members, whose constituencies – the Ilakas – are comprised of a handful of VDCs or more, in the range of 20.-30.000 people, typically need to move about for resources several days a week. Many DDC Members explain that being this active, even their family economy is affected quite a bit.

Is getting “power”, then, not motivating all the activity, too? Well, many local politicians will tell you that getting a position – and the status and opportunities it offers – sure matters. Some will even say money plays a part. But power and money, most insist, are only two of the motives that drive them.

Chapter 13: Candidate Selection

Candidate selection – whatever the motives of the local politicians might be – is a time of great competition in all the parties, also at local level. There are typically hundreds of aspiring candidates but only few positions to get! If getting power were your sole motive, you would soon get frustrated.

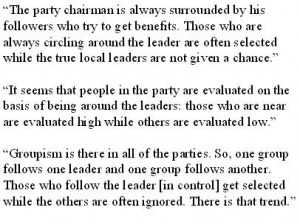

Many local politicians wait in vain for a the party ticket. Indeed, most will remain in a lower position for their entire career! However, many are still acutely focused on who is selected and how. First off many will tell you that to be selected, you have to be a runner and to have “worked for the people”.

It makes sense, doesn’t it? If you want to be selected as the party’s candidate, you first have to show that you enjoy a certain amount of popularity in the constituency; and to enjoy popularity or support at least in part of the constituency, you need a local reputation as someone who will help.The more you’re known as a politician whom supporters of the party can go to for help, the more you’ll be able to mobilise support in the election. People will think: “Since we are his supporters, if he gets into power he can do even more for us”. In fact, local politicians often appreciate this role.

However, many local politicians add that politicians who have not done much service for the “people” are, in fact, also selected as the party’s candidates. Does that really happen? Well, according to many local politicians it happens quite a lot. The effort as a runner is not the only selection criterion!

Candidate Selection: Other Selection Criteria

Education or profession can both play a role in candidate selection. You might be less active as a runner. But if you’re the most educated person in the constituency, perhaps trained as a lawyer or journalist, college teacher or business manager, you have other qualities that the party might value.

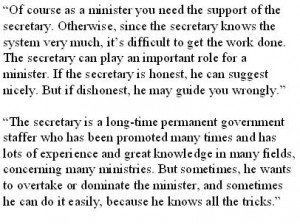

Just take the example of a young lawyer who was busy in his profession, and therefore had less time to be a “runner” in any matter that locals brought to him. The party selected him as a candidate for the local DDC Member position, in great part because he could help the party in judicial matters.Seniority also plays a role. Go to any party and you’ll find examples of the party selecting not the most active or even popular candidate but the one who has served the party for the longest time. The longer you have worked for the party and built a reputation within it, the greater your chances.