Here’s excerpts from our Crash Course on Local Politics in Nepal on the lack of financial capacity in the local government bodies and their high dependence on central-level funding up until now.

Chapter 5: Capacity and Power of Local Governments

The local parties are all urged to use the capacity and power of the local governments to serve the people as a whole. That’s a major public demand. Ask anybody, and most will reply on a general level that the local politicians ought to use their power to make “development” across the district.

But what is the capacity and power of local governments in Nepal to “develop” a whole district: to meet all the needs and interests for roads, electricity, drinking water, schools, health posts, and so on? Well, we’ll have to distinguish here between two periods: before and after the fall of 2002.

Capacity and Power of Elected Local Governments

Up until 2002, which was a year when not only local governments but also parliament itself were dissolved and replaced with appointed officials, their capacity and power did increase. In fact, much was achieved in the area of “devolution”: the transfer of power and resources to the local level.

A UML-led government took the first step in 1994 as it raised the annual block-grant for the VDCs from less than 1 to 3 lakh. One year later, the successive NC government trumped this gesture by raising the amount to 5 lakh or 500,000 rupees. Also the DDC grants were raised during this period.

In addition to that, and strongly promoted by donor agencies, the Local Authorities Act was replaced with the Local Self-governance Act. This act gave the DDCs and VDCs certain further powers, including powers to collect more taxes and to organise committees to carry out the work.

However, the DDCs and VDCs remained left not least with grossly inadequate financial capacity to effectively handle the responsibilities assigned to them and to meet local needs and expectations. Indeed, the 5 lakh to the VDCs was a major improvement. But in a whole VDC it’s a small amount.

5 lakh is enough to build a couple of average size classrooms and pave a stretch of road. However, if what you want is to provide services and infrastructure in all the nine wards in a VDC, and if you’re also trying to make bigger infrastructure like a high-school or a health post, it is inadequate.

As a result, it often takes several years to complete a bigger project in a VDC simply because the 5 lakh will only cover part of it. Take a school building. One year the VDC will do the walls and part of the roof; the next put in furniture and start teaching; and the third year maybe install the toilets.

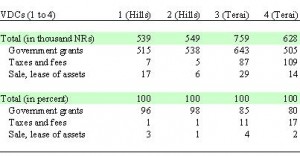

It’s true that a strengthening of the fiscal powers of the local governments occurred. The Local Self-governance Act gave the DDCs and VDCs authority to raise and keep more and new types of local revenue. But on the whole, local revenue, especially at VDC level, has remained quite limited.

The DDCs collect revenue mainly from road tax and extraction of raw materials on DDC land. In most cases, contractors are given the tasks and pay a percentage of the revenues back to the DDC. VDCs mainly collect land tax. But due to a small tax base in many areas, local revenues are small.

In sum, most DDCs and VDCs lack the financial resources to effectively meet the numerous and typically basic needs in their areas: needs such as more classrooms, health posts, teachers and medicine, electricity and drinking water, and much more. Every year many needs are left unmet!