The six provinces as proposed by the four main parties, now changed to seven by splitting the far-western province into two

What does the constitution tabled at present entail for local Nepal? Well, it’s hard to cover it all – the draft document stands at 104 pages plus appendices – but essentially it looks like much will be different in the future, although much will also remain the same. The overarching issue is indeed the creation of a new sub-level of government: provinces. The draft constitution provides for eight provinces – later the four main parties for some reason decided on six, now gone up to seven provinces – but numbers aside: what is a province?

The 75 districts (with colour-indication of Nepal’s five regions) hitherto the intermediary level between Kathmandu and village/town level

Well, provinces will come to constitute a sub-level of government hovering over the “local level”. With seven provinces – and the current 75 districts – provincial governments will each have, say, 10 to 12 districts under them, depending on the final delineation of provincial boundaries. They will have the right to collect certain taxes and fees, to make provincial laws, provided they coordinate with federal law, to employ staff through a provincial-level Public Service Commission, and to distribute funds.

Big deal in the draft constitution: ethnic group in majority – such as Tharus – may change the official language in a given province to their own

It’s not clear, though, how independent or “autonomous” the provinces will be. One issue sounds like a big deal, if in fact implemented. Provinces will be entitled under the draft constitution to make the dominant language in their own area the local official language! If Tharus, for example, are in majority they can decide to replace Nepali with Tharu as the language spoken and written at the provincial offices. They have to apply to a central language commission first – but still, it’s laid out as a real possibility! Other provincial powers, however, come across as a lot more limited.

There always were three tiers of government – but now district, village and towns are lumped into one

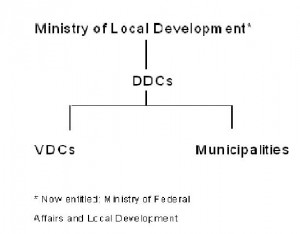

The provinces will preside over the local level in a certain sense. But first of all, what will the “local level” comprise? Well, it’s everything below the provincial level. Curiously enough, the draft constitution says that Nepal will have “three tiers of government“: federal, provincial and local. But until now, there always were three tiers of government: central, district and local level. With the stroke of a pen, however, district level and local bodies at village and town level – organisationally positioned below the district – are now lumped together as one “local level”.

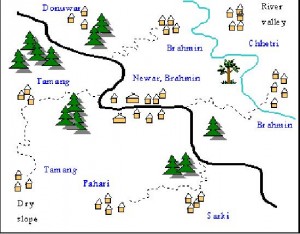

What a VDC typically looks like: numerous villages inhabited by different castes and ethnic groups – now renamed village municipalities

So, how are formal relations between federal, provincial, and local level envisaged to be cut out? Well, starting with the basic terms first, Village Development Committees (VDCs) are to be renamed “Village Municipalities”, VDC Chairman and Vice Chairman are now to be addressed Municipal Head and Deputy, and a central-level special commission on local affairs is going to re-delineate local boundaries, possibly with a view to making larger entities. The government will then decide on the division of responsibilities in detail only later on.

Provincial and local bodies get lots of responsibilities for roads and other sectors: but how to fund it?

But it’s already made clear in the constitution by now that provincial and local governments will be empowered – and indeed required – to make plans and budgets for development work, each at their level, manage various sectors like roads and electricity, oversee courts and police, and more! Who is going to perform which tasks, and to what extent, is to be decided later on. Indeed, few constitutions would go into detail with such matters – it’s for law to define. But it already stands out that there’s a lot to do, and looking at the many responsibilities, one overall question arises: how will the lower levels be funded?

The question of funding is dealt with to some loose extent in the draft constitution. Province, district, village and town bodies will all be equipped with various authority to collect taxes and fees. The list includes more or less the same types of taxes and fees as defined in the law right now: land tax, property tax, road tax, various registration fees, just to mention the main ones. However, the difference lies in the fact that now these same taxes and fees will have to help finance not only local bodies – as before – but also the provincial governments!

Will local taxes be enough to fund provincial government as well? Well, if the previous setup is anything to go by, clearly not. Central – or “federal” – government will have to fund most of the public expenditures at local and provincial level. Indeed, the draft constitution says that the government in Kathmandu will continue to portion out funds to lower levels just like in the past. A commission will recommend which provinces to give more or less with a view to secure equality. But the central level will decide how much provincial governments will receive!

The question of ethnicity and language – rather than division of power and resources – has dominated the debate

The provinces are not envisaged as powerful “states” in the draft constitution. While the issue of ethnicity and language has strongly dominated the debate so far, the division of power and resources between central and local level has attracted much less attention. Why it’s like that may have to do with many things, and we’ll leave the question wide open. But what’s clear is that while the draft constitution will create provincial governments, perhaps even with their own official languages, it does little to genuinely decentralise power and resources!

Relations of power between central and local level unlikely to change as long as

the parties remain centralised: party leaders in Kathmandu

Budgetary control – above all control of foreign aid money – remains on central hands. Add to that the structure of decision-making within the political parties – which is still highly centralised around the party leaders in Kathmandu – and any deeper change in the division of power and resources between central and local level can seem quite unlikely. It’s also true, though, that once the provinces are created; politicians and bureaucrats get established; and ethnicity, perhaps, is invoked, new things might happen.

Provinces can surely become a basis of claims for more power and resources vis-a-vis central level – just as it can relative to other provincial governments where different ethnic groups are in majority – and as some form of provincial politics emerges, who knows what kind of change that might all foster.